New data tools being developed in Wisconsin and elsewhere aim to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

One of those tools was created under the direction of Elizabeth Burnside, a radiology professor at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health. She spoke yesterday in Madison at the Wisconsin Biohealth Summit, organized each year by BioForward.

Burnside and other speakers noted the number of available medical data is growing at an increasing pace, making it all but impossible for clinicians to keep up with the latest findings.

“What I’ve dedicated my career to doing is developing artificial intelligence algorithms and techniques in order to manage this overwhelming amount of data,” Burnside said.

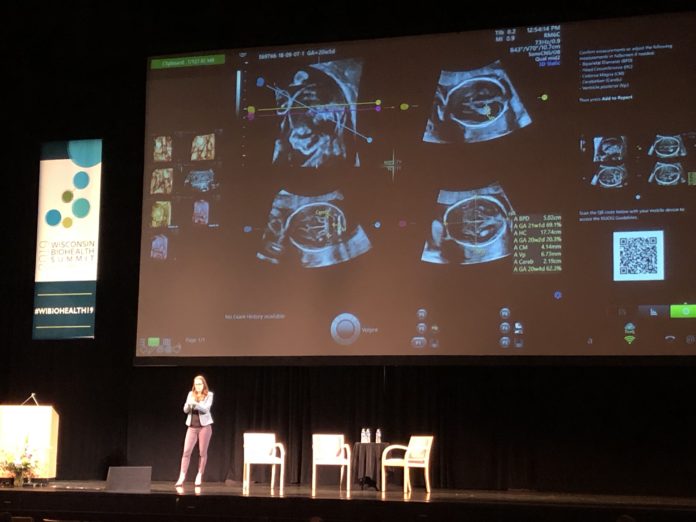

One way to offset the mounting expectations placed on care providers is to automate portions of the tasks they perform. Karley Yoder, director of product management of AI analytics with GE Healthcare’s digital care division, described how software developed at the company is improving the process of taking ultrasounds.

“This algorithm, embedded directly within the device, automates detection steps that people would have had to perform before,” she said. “Taking those 41 steps down to eight steps, improving your throughput by 80 percent, but more importantly, increasing accuracy by 40 percent.”

She said this application helps clinicians focus more on the task of ensuring fetal and maternal health, rather than collecting information.

“It’s going to take many examples like this, where we can drive better patient and provider outcomes, if we’re going to drive toward that vision of precision health,” Yoder (pictured here) said.

In partnership with computer scientists and informaticians at UW-Madison, Burnside began constructing a database around 10 years ago that compiles data on breast cancer, in hopes of improving outcomes for this relatively common cancer.

One in eight women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime, according to Burnside. Over a 10-year period, she says about 450 million women will get a screening mammogram, and another 200 million will be eligible but won’t undergo the test. She said just under 3 million women will be treated for breast cancer over a decade.

“We at the University of Wisconsin want to learn from every one of those experiences,” she said.

The database she pioneered now contains data from over 40,000 women, including 120,000 mammograms, 10,000 ultrasounds, and 3,000 breast MRIs. And she’s developed algorithms that can use all that information to make accurate diagnoses.

She explained the success of algorithms like these is based on how many accurate diagnoses they can make and how many false positives occur. Compared to the radiologist, she says the diagnostic algorithms can improve these measures “to a statistically significant degree.”

“We can improve both the sensitivity — the accurate diagnosis — as well as the specificity, or decreasing those false alarms,” she said. “In the 90,000 women that we trained this algorithm on, it would have resulted in almost 40 accurate and earlier diagnoses… and over 4,000 decreased false alarms. That’s important.”

Yoder noted that in 2010, health care data was doubling roughly every 3.5 years. But by 2020, she said it’s expected to double every three months.

“So the data that we have, and the power that we have to do something with that data, have primed us to use deep learning and AI in the field of health care,” she said.

As another example, she said GE Healthcare is exploring the use of AI in scanning parts of the spine, reducing the time required for one procedure from more than an hour to five seconds.

“Just let yourself imagine what we can do across health care when we apply AI to data creation itself, and put more quality data out there into the world for clinicians and AI to interact with together,” Yoder said.

–By Alex Moe

WisBusiness.com